Luna Yue Huang

Economist / Data Scientist

Resume | LinkedIn | GitHub | Scholar

Mapping Historical Climate Migration With 1.6 Million Aerial Photographs

(GitHub)

In a dusty room of the UK National Collection of Aerial Photography sit millions of black-and-white aerial photographs. Taken over parts of Africa and the Caribbean, they were meant to serve reconnaissance purposes after the second world war, but by accident became a precious scholarly record of our planet in the 1940s-70s, before the advent of modern satellite imagery. However, unscanned and unindexed, they were never used by the research community, or appreciated by the public. Our team took on the challenge to recreate a “historical Google Earth” from these photos.

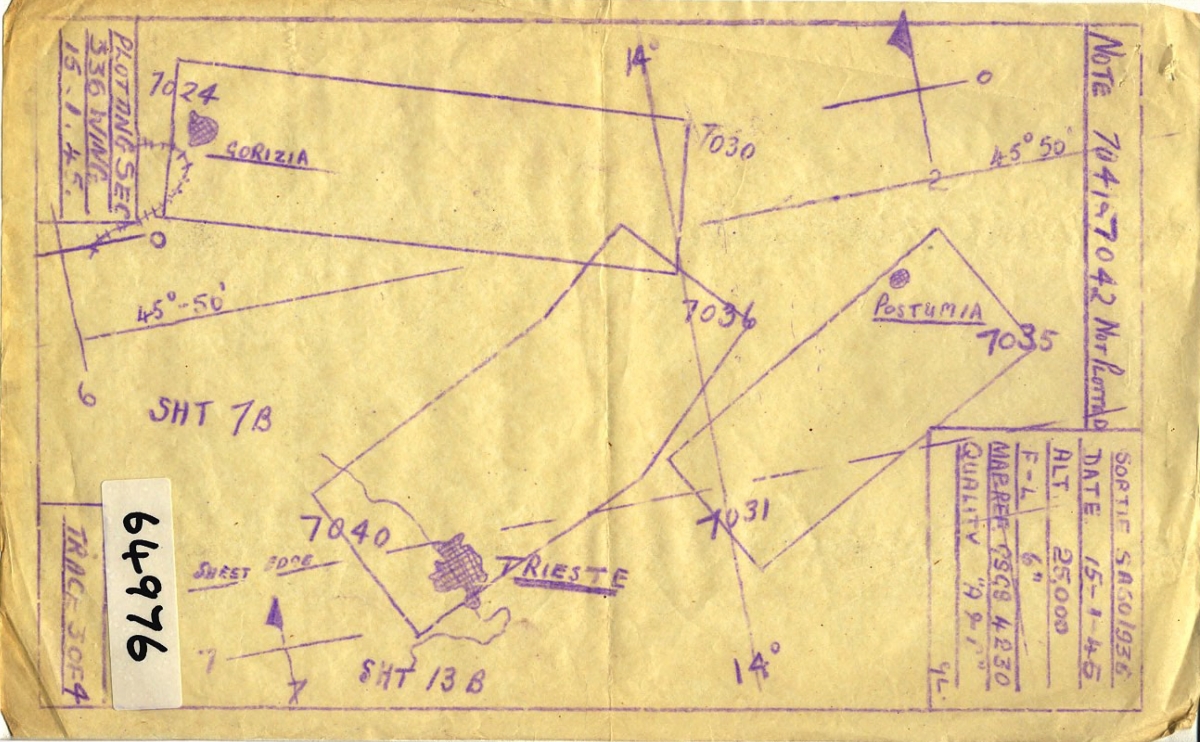

Figure 1: The positions of four aerial photos are jointly optimized to form a coherent mosaic.

Source: Historical England1.

Figure 2: Boxes of historical aerial photos, stored in the National Collection of Aerial Photography, UK.

Source: National Collection of Aerial Photography, UK.

Source: National Collection of Aerial Photography, UK.

Our team has been studying how climate change might set off mass migrations around the world, and looking back to history for inspiration. When we learned about this archive, we were immediately excited. These century-old photos can provide crucial new insights to this question because they could reveal how populations responded to natural disasters in the past — specifically, a series of extreme droughts that plagued Africa, and hurricanes that wreaked havoc in the Caribbean islands. There were such little census or survey data back then, and the earliest record of satellite images started only in the 1970s. Apart from these boxes and boxes of black-and-white photos, scholars trying to study historical mass migrations have almost nothing to work with, but now, we may be able to observe human settlement patterns from these photos and study how they respond to extreme weather events.

One of the first challenges in working with historical aerial photos is that it is difficult to georeference them, or to assign the images to the geographical location that they cover. Unlike modern satellite imagery, historical images are not georeferenced at the time when they are collected, and the ways that experts record their locations can be pretty crude. Usually, they roughly outline the areas that the aerial photos cover by hand, and mark the image identifier numbers on them. As you can imagine, these hand-drawn maps tend to be inaccurate, and more importantly, georeferencing aerial photos solely based on hand-drawn maps is labor-intensive and quickly becomes impossible as the number of aerial photos grows. Other commercially available software such as Photoshop and OpenCV succeeded in automatically stitching a small number of images (<100), but failed miserably when scaled up.

Figure 3: An example hand-drawn map marking the positions of the aerial photos.

Source: National Collection of Aerial Photography, UK.

Source: National Collection of Aerial Photography, UK.

I developed an algorithm that utilizes information from these coarse hand-drawn maps and automatically positions aerial photos such that they are aligned with each other. The algorithm takes inspiration from both classic computer vision algorithms such as SURF and RANSAC, and machine learning concepts such as computational graph and gradient descent. See Figure 1 for a simple demonstration; more detailed descriptions and the source codes can be found here.

Currently, our team is extracting historical building footprints and road networks from these mosaicked images, with state-of-the-art deep learning models such as DeepLabV3 and D-LinkNet. Through that, we are tracing the changes in human settlement patterns over time, and studying the causal effects of long-term climatic changes on the spatial distribution of the human population.

-

This aerial photo does not belong to the historical archive used in this project. For legal reasons, we could not share the actual photos until a later date. ↩